Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS | More

Sources & Resources #1: The Everyday War

Presenter: Nicole Davis

Further information and links: The Everyday War web resource

Creature Feature #1: Frogs

Presenter: Professor Andy May

Interviewees: Associate Professor Andrea Gaynor, environmental historian, University of Western Australia; Associate Professor Kirsten Parris, urban ecologist, The University of Melbourne

Further information and links: Climate — Confectionary— Frogs — Natural Environment — Rivers and Creeks

Can We Help? #1: Christopher Morris

Presenters: Amelia Curran & Ross Karavis

Further information and links: Greeks — Hawthorn — Head of the River — Rowing and Sculling — Yarra River

Credits

Series Host — Professor Andy May

Episode Presenters — Nicole Davis, Andy May, Amelia Curran, Ross Karavis

Audio Engineer — Gavin Nebauer

Music — Andrew Batterham, “And there I was”

Transcript

Welcome to My Marvellous Melbourne, a podcast of the Melbourne History Workshop.

Hi there — I’m Andy May. In this episode, our Creature Feature lifts the lid on the humble frog; Amelia and Ross answer a listener query that takes us up the Yarra River in the nineteenth century; but first, Nicole tells us about a new resource on the history of World War One on the home front in Melbourne.

SOURCES & RESOURCES #1: THE EVERYDAY WAR

Presenter: Nicole Davis

Hi — I’m Nicole Davis. We’ve recently seen major commemorations of the First World War, one of the twentieth century’s most dramatic and disruptive events. But actually, the majority of Australians didn’t experience the war on the far-flung battlefields of Europe, but at home, in very everyday ways, in the cities and towns where they lived and worked.

Daily life in Melbourne was filled with events that brought the war close to home. Public entertainment, economic prosperity, the day-to-day running of the city, international trade relationships, housing and health— all were to be shaped by this conflict.

So how can we get a clearer sense of some of these experiences? Well, recently we’ve digitised a selection of records from the City of Melbourne archives—around 6000 pages in fact—so you can explore these stories of the Everyday War for yourself.

The Council was involved in numerous ways in the war: it raised money for ambulances, encouraged enlistment, and distributed recruiting posters. The growing visibility of the military as the war progressed is evident in council files through discussions of marches and other war-related activities.

Let’s dig a little further into some of these letters.

So in August 1914, Mrs J Graham writes to the Council requesting use of the Kensington Municipal Buildings to hold a Euchre Party in aid of the Patriotic Fund. A month later, the importers of the Gestetner Rotary Duplicator ensure the council that despite his German-sounding name, D. Gestetner is in fact an Englishman, and the products are made at Tottenham Hale in England. Another small note records the council’s deep regret on news of the death of yet another of its employees—this time, William Williams from the Electric Supply Department, who was killed in action in German New Guinea. A handbill for the Southern Cross Tobacco fund reminds readers that “something to smoke is the comfort asked for more frequently than any other in letters from the front”. The Victorian Football Association was also involved, sending notification in 1916 that it has decided to abandon its matches during the currency of the war.

Another letter from the Department of Defence suggests to the Lord Mayor that rather than giving the privilege of selling foodstuffs and flowers in the streets of the city to foreigners, that they might think of giving preference to returned soldiers instead. Another man, James Livingston, wrote to complain about pro-German agitators haranguing crowds in Carlton Gardens; but in the same file, we find another man J.H. Beecham taking a different view. He cautions the police against cracking down on freedom of speech, so as not to “penalize many of the old pioneers, whose only source of enjoyment for years past, has been to listen or join in the discussions in these gardens”.

Finally, another letter from William Lee, representing the Licensed Motor Drivers & Cabmen, hearing that the council has granted a licence to a woman, sent “a strong protest against” what he saw as a “degradation to womanhood and humanity”. He says: “There is a vast difference, between ladies, or women, being granted a driver’s license for motors, and one licensed to drive one for hire in the street… We are not England, where the man power shortage has brought out patriotic women to fill places in buses, trams, etc., and there is no reason that women should be allowed to hold such a license and offer a chance to the abuse and humiliation, that will certainly come their way.”

Times have certainly changed, as we can see from this, but these records, and almost 600 other files, help us to make a fine-grained analysis of changing attitudes that are not easily reducible to simple labels of enthusiasm or patriotism. ‘In wartime’, as historian Jay Winter challenges, ‘identities on all levels… the individual…the city, the nation—always overlapped’.

Dive in and have a look—I’m sure you’ll find something surprising.

CREATURE FEATURE #1: FROGS

Presenter: Professor Andy May

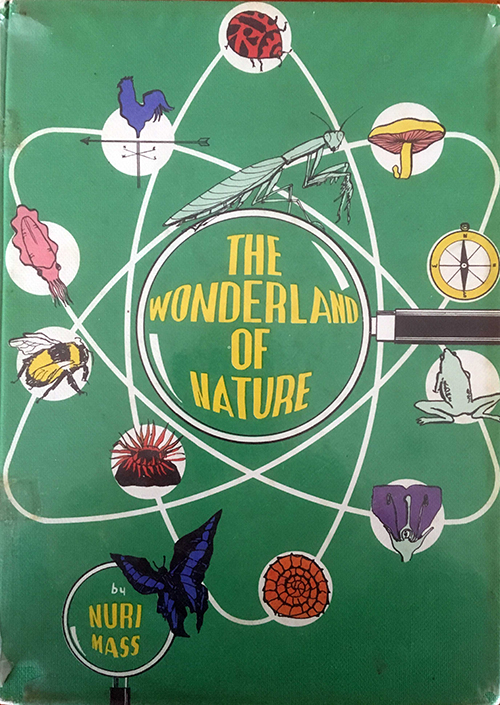

When I unwrapped my presents on Christmas day in 1968, I found to my delight a copy of The Wonderland of Nature, written and illustrated by the exotic-sounding Nuri Mass. The lime-green cover design featured the kind of diagram usually used to show atomic structure—in the nucleus was a magnifying glass that warped the book’s title under its lens, and astride it sat a proud praying mantis, its front legs folded up in classic pose. The electrons that whizzed around the perimeter were in turn a compass, a mushroom, a ladybird, a weather vane, a cephalapod, a bee, a sea anemone, an ammonite fossil, the cross section of a flower…and a frog.

The 1960s was a decade of big science — the space race, plate tectonics, the computer, the nuclear age. In a little over six months time I’d watch the moon landing on our next door neighbours’ black and white TV. But although physics was the zeitgeist of the age, Nuri Mass had delivered this suburban boy a universe in his own backyard. In a family of science boffins, I was always more likely to get a book than a barrel of monkeys as a present. The back-cover blurb of this new addition to the May library claimed that here was a book ‘written and produced in Australia for Australian children’. I don’t expect that my six-year-old self quite understood the subtlety of the nationalist agenda, but whatever the case, Nuri Mass had somehow read my mind, and the minds of my two older brothers, my naturalists in arms.

Nuri Mass was born in Richmond in Melbourne in 1918, and after a stint in Argentina, came back to Australia when she was twelve, and later studied in Sydney. Disillusioned with the lack of encouragement for Australian writers, she set up her own publishing house, and the first edition of The Wonderland of Nature rolled off The Writers Press in February 1964.

Much of the book was about insects, but one of the creatures orbiting around that central magnifying glass was a green frog. “At some time or other”, she wrote, “every boy and girl catches tadpoles, and hopes to be able to keep them until they turn into frogs. Have you? If not, you should try to, because a frog is one of the most interesting things in Nature, and the way he changes from a tadpole is really wonderful”.

OK, so we already knew this miracle, but it was great that some expert adult also thought it was pretty interesting. Our street was in an outer eastern suburb that boomed in the postwar decades, its housing subdivisions still punctuated by seasonal watercourses and remnant bush blocks. So it was that we stalked ducks in the creek just down the road, now a barrel drain; we collected longicorn beetles and emperor gum caterpillars off the mahogany gum in the paddock next door, now long since built over; and we fished for taddies in swampy ground at Koonung Creek using a plastic kitchen colander that dad had lashed to the end of a length of bamboo, on land later bulldozed for the Eastern Freeway extension.

And we brought them home, our amphibian friends, and the gelatinous frog spawn too, which we kept in old ice cream containers and yoghurt pots in the back verandah, and as the tadpoles took shape we fed them on boiled lettuce leaves, waiting for legs to sprout, and eventually set them free in one of the ponds in our back yard. Any day I could lift up a rock or two around the pond and know that everything was in its place, that you could always find a frog when you wanted one. And they were part of the soundtrack to my suburban childhood. On those sticky summer evenings with the louvre windows open to catch a whiff of breeze, we were sent off to sleep to the pulsing rhythms of their chorus.

That’s just my memory. You might have your own, from your childhood days around the creeks and waterways of the spreading city, or the dams and swamps of the outer rural fringe. You might remember chasing frogs on weekends or Show Day holidays, in Coburg Lake or the disused quarry pits of East Preston and Frankston, or maybe just in the drain behind the Post Office at Williamstown.

Frogs meant other things to kids as well — in 1930, at the Great White City, Macpherson Robertson’s confectionary factory in Fitzroy, where on still days the back lanes were suffused with the scent of chocolate, nineteen-year old Harry Melbourne thought it might be a good idea to produce a chocolate in the shape of a frog rather than a mouse. Everyone knew kids loved frogs, and they were just a bit more mother-friendly than rodents. And so the Freddo Frog was born, a Melbourne invention in more ways than one, in twelve different flavours, the best penny chocolate of 1940. When Harry died at the age of 94 his coffin was draped with a Freddo Frog flag.

I haven’t seen a frog in any of my back gardens for many years now, but that’s not to say that small boys and girls don’t stalk them still in the liminal and littoral spaces of greater Melbourne. Frogs could be surprising fun, placed under a sister’s pillow or in a classmate’s lunch box. The late educationist and historian Barbara Falk once told me how as a girl she and her friends would sneak into St Patrick’s Cathedral and put frogs in the holy water to scare the Catholics.

The postwar decades seemed to be some kind of turning point for the frog. Where small children loved their slimy mystery, mothers fretted about their kids falling into creeks and flooded quarry pits, and especially in the 1950s, the new residents of the ever-expanding suburbs saw frogs as a nuisance and a curse.

An eleven-year-old Kwong Lee Dow from Burwood—later to become founding senior lecturer in the Centre for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Melbourne—wrote to the Age in 1949 about how he bred tadpoles in his spare time. In 1953, out at Happy Hollow Farm on the Plenty River in Greensborough, twelve-year-old Christopher Bell found a tree-frog in his canoe, named it Algernon, and kept it as a pet. As he wrote in a letter to the Weekly Times, he marvelled as it changed colour from fawn to brown to green. Christopher grew up to be a medical scientist who worked for part of his career in the department of physiology at the University of Melbourne.

Both of those frog-loving boys won a ten-shilling prize for publication of their letters—which was more money than you could make out of frogs in any other way in Melbourne at that time. When the summer heat dried up its worm pits and frog breeding grounds, the Melbourne Zoo used to advertise for entrepreneurial boys to supply buckets of worms and frogs and yabbies to feed the hungry platypus and the reptiles that emerged starving from their winter hibernation: the going rate in 1950 was two shillings for a jam tin of worms; between sixpence and three shillings for a dozen frogs, and sixpence a dozen for yabbies.

But in the 1950s, frogs were often used in the same sentence as mosquitoes and smells, as symbols of the heartbreak suburbs where housing construction outstripped proper drainage and sealed roads. From the swampy ground in Brighton and South Melbourne to the water-logged sand pits of Springvale. From Deer Park on the Keilor Plains to the grassy ground at West Heidelberg, where tiger snakes gorged themselves on the frogs that bred in the drains. As the Elwood canal flooded the housing developments that grew up at its margins, and the Maribyrnong broke its banks, again, the sound of frogs croaking was now the signal of poor urban infrastructure rather than the siren of bucolic bliss.

Murrumbeena, according to one version of the name, comes from an Aboriginal word meaning ‘land of frogs’. As the city spread east and west, north and south, the gentle and mesmerising sound of the frog became a clamour rather than a lullaby. People couldn’t sleep from the hullabaloo of frogs in Chelsea. A resident of George Street Highett took a neighbour to Court because she couldn’t sleep from the noise of frogs breeding in pools of water that he’d allowed to gather by their fence line. A resident in Deals Road Clayton South complained that she couldn’t hear the radio for the noise of frogs congregating in the water pumped from the local sandpits. As the suburbs spread, the frog switched from a simple beauty silhouetted against a backdoor fly-screen at dusk, to a nuisance in the backyard swimming pool.

But the frog could also be educational as well as fun— the child migrants knew it as they kept frogs and lizards in tins under their beds, away from the watchful eye of the superintendent at the newly-opened Orana children’s home in Elgar Road Burwood. At the same time, along with the latest in scientifically designed school architecture with radiant floor heating and tubular desks, the young ladies at Tintern Girls Grammar School in East Ringwood were privileged to have a new school that boasted a wildlife sanctuary and a frog pond to encourage outdoor as well as indoor education.

In these immediate postwar decades, before Nuri Mass promoted the wonders of natural history to suburban boys and girls, other naturalist like Crosbie Morrison charmed the readers of his ‘Backyard Diary’ column in the Argus: “Cicadas are still with us”, he noted in November 1954, “taking up the chorus in the morning where the frogs leave off, and continuing almost until the evening, when the frogs start up again”.

Let’s hear a little more from a historian and an ecologist about how things are shaping up for the frog in the Melbourne of today. I’m speaking here with Andrea Gaynor, an environmental historian from the University of Western Australia in Perth, and Kirsten Parris, an urban ecologist at the University of Melbourne.

AM: Now look, the frog seems to be a creature that once we took for granted, it seemed to be ubiquitous and in everyone’s backyard or local park, but now it’s sort of the poster animal for ecological fragility. So how did that change happen in a fairly short space of time?

AG: I guess the thing that contributed most significantly to the timing of the frog becoming this poster child for ecological awareness was the decline in frog numbers that scientists started noticing in the 1970s and 1980s and really accelerated into the 1990s. So, by 1990 frogs were listed as a category of animal that was in decline, and in the mid-to-late 1990s we discovered that the chytrid fungus, which is a fungus that affects amphibians, and quite severely in some cases — particularly upland amphibians — had arrived in Australia.

They also are an indicator species, so because they are very sensitive to their ecological surroundings, because of their porous skin and the way that they breathe and live, they are very sensitive to pollution, they’re very sensitive to temperature change, to drought. Ecologists regard them as an indicator species of general ecological health. So, with the rising ecological awareness in the 1980s and 1990s, frogs became an apt symbol for all of the changes that people could see going on around them, in terms of increasing pollution, the ‘greenhouse effect,’ now known as climate change of course. The fact that they’re green, I think, really helped; they were associated with being green, being ecological.

AM: I think in the early 2000s, when the Western Ring Road in Melbourne was being constructed, they had to bypass a patch where the growling grass frog was abundant. You can tell us a bit more about the growling grass frog, I think?

AG: If you look online you’ll see people who remember, for example, them being very abundant in Reservoir in the 1960s; they were in every drain, you know, every time it rained they would be flopping about on the road, and they’re quite a large frog, so they’re hard to miss. They did decline probably through a range of these threatening processes again, so urbanisation, loss of habitat, and the chytrid fungus as well. And probably also changes in rainfall patterns, I think.

AM: So when we think about — for those of us of a certain generation in Melbourne — our childhoods when we did go hunting frogs and so on, and we think that now we haven’t seen a frog for a while, that’s not just an act of nostalgia perhaps; there really is a decline in population?

AG: Yeah, absolutely, absolutely. They have declined very dramatically in a very short time. So it’s something that people have noticed; it’s happened within living memory.

AM: So what other ways have humans encountered frogs in urban settings?

AG: There’s been some frog events in Melbourne. For example I was looking through Trove, and found a report of a frog — what would you call it? — I guess if you were being Biblical you’d call it a frog ‘plague,’ but it was masses of frogs emerging after rain. This was in 1938, and the report was that they were appearing in their thousands between Oakleigh and Dromana, in the south, and crossing the roads, heading west.

AM: I’ve read similar reports in historical newspapers, and also about — I don’t know whether these are apocryphal or not — of showers of frogs, reports from the papers of people driving from Geelong to Melbourne and encountering downfalls of frogs. Does that actually happen?

AG: No, that is a thing apparently. I think they are drawn up through water spouts, somehow, and you’ll get showers of frogs and showers of fish as well. A frog-free future would I think be a very sad thing, but they are a canary in the coalmine, and point to the imminent or the urgent need for us to learn to live more sustainably.

AM: Why did the frog cross the road? Well, it didn’t — it was run over half way. I wonder if that sums up the fate of frogs in cities? I’m talking here with urban ecologist Kirsten Parris.

KP: Certainly the construction of roads is a big problem for frogs and other small animals that need to move across the landscape. There is quite good information about the relationship between the volume of traffic on the road and the probability of a frog being squashed before it makes it to the other side. And once you get above about ten thousand vehicles a day, it’s pretty difficult for your frog to make it safely across. Roads in urban environments cause habitat isolation for frogs. They can be in happy pockets of habitat, but if these areas are separated by roads it’s very difficult for the frogs to move from one place to another. We have a case around Melbourne of one of our threatened frog species, the growling grass frog, and it lives to the north, west, and south-east of Melbourne, right where our new urban growth corridors also happen to be, so there has been some work to construct tunnels or spaces under roads for the frogs to cross. We don’t really know whether they will use those spaces though.

Another issue which that brings me to is the issue of road noise in cities. Noise is a problem for humans, it disrupts our sleep, it makes it difficult for us to hear each other, and it also has the same effect for other wildlife that communicate using sound. So frogs call to each other, birds sing, all of those groups of animals have problems hearing each other in noisy cities. If we’ve got lots of male frogs out there calling their hearts out and using a lot of energy to make that sound, but the females can’t hear them, then that’s a problem for population persistence. At the moment we’ve demonstrated that female frogs do find it difficult to hear male frogs in cities, and the distance over which they can hear them can be reduced by up to 90%, so it’s pretty dramatic.

If you’re walking around in the wintertime, you would hear the southern brown tree frog and the common eastern froglet. The southern brown tree frog is an urban survivor frog and does very well even in the very centre of the city, so you could hear that frog calling in the Carlton Gardens, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Queen Victoria Gardens, just across from the Arts Centre. And then in spring we have the marsh frogs, so the ‘pobblebonks’ — they go ‘bonk bonk, bonk bonk bonk’ — the striped and spotted marsh frogs are active then. Then in summer the growling grass frog and sometimes, depending on where you are in Melbourne, we also have the emerald spotted tree frog, and that likes a warmer night for calling.

The growling grass frog that I mentioned earlier is struggling, particularly with increasing urbanisation, and a colleague of mine, Geoff Heard, has been studying this frog in northern Melbourne, around the Merri Creek corridor, since probably the early 2000s, and in that 15-year period we’ve lost probably 20 or 30% of the population. And that’s likely to continue with increased urban development, with the new urban growth areas of Melbourne, wetlands that are away from creek corridors are nearly all going to be destroyed for housing.

I think it’s fun to find when nature is still persisting in the city, because often people just assume that, well, now that there’s so many people — we’ve got 4 million or so people living in Melbourne — there’s not really space for nature anymore. But if you look in particular parts of the city, you can find frogs as well as many other groups of animals still persisting, and I think that’s really fun.

AM: Scientists tell us that frog numbers have been on the decline since the 1980s; eight species have become extinct, and a further 20 are under serious threat. My account of the frog is marbled with nostalgia, of course, but when I was a kid, there did always seem to be a frog if you wanted one. If I close my eyes and cup my hands just tight enough to enclose, but loose enough not to smother, my muscles still hold the memory of that wet and jumpy life between my palms. I can’t imagine a world without them, under a rock, lurking somewhere in Melbourne’s greenery.

CAN WE HELP #1: CHRISTOPHER MORRIS

Presenters: Amelia Curran and Ross Karavis

AC: Hi—I’m Amelia Curran, and with Ross Karavis we’re helping out with a query that’s come in from Chris Morris, who is researching details of his family history on his father’s side.

RK: Chris’s great grandfather Christodoulos Moros—or Christopher Morris as he was known in Melbourne—was born in Greece around 1834, and died in Hawthorn in 1885. Chris tells us that Christodoulos arrived in Australia as a ship’s carpenter.

AC: Of particular interest to Chris is his great-grandfather’s boat hire business on the Yarra in either Hawthorn or Richmond, and he’d like a bit more information about this part of his life. We’ve got a few clues to go on—his 1867 marriage certificate notes that he was living in Sandridge, which of course is the old name for Port Melbourne, and his occupation was recorded as “mariner”.

RK: Well Sandridge might be a logical place for a salty sailor type to be hanging out. Chris sent us a copy of an intriguing document, and the first thing we can do is give him a little bit of help working out what it says. It’s actually a certificate issued in Paros, Greece in 1864. The harbour master certifies that in accordance with the power invested in him by the Greek state, he can certify that Christodoulos was an emboronaftis, or a merchant sailor.

AC: Chris also knows that his great grandfather at some point had some kind of boat hire business in either Richmond or Hawthorn. We know that in that era before motor cars, a cheap and popular outing was to take river cruises on the Yarra, and boats regularly plied from Princes Bridge up to the Hawthorn Tea Gardens, which were on a site under the Wallen Road bridge. So the likelihood is that Christopher Morris was involved in this trade. But we’ve found a couple of snippets that do in fact place Christopher further up the Yarra River.

Now if you hung around the Yarra River for long enough in the nineteenth century, you were bound to come across a drowned body or two. I’ve had a look at some inquest records and sure enough, Christopher Morris, boathouse keeper at Hawthorn, found a body entangled in the willows about fifty yards above the bridge in 1883. In the man’s pockets was a bottle of colonial ale, which might be a clue as to how he ended up in the river.

RK: Hawthorn Bridge was opened in 1861 connecting Richmond and Hawthorn, and it’s the earliest surviving major metal bridge in Victoria. Hawthorn Rowing Club formed in 1877, and according to the club’s history it has “always operated from the part of the Yarra River that flows under Hawthorn Bridge in Bridge Road connecting the suburbs of Hawthorn and Richmond”. Melbourne Directories in the 1880s also record Christopher Morris as living on the south side of Burwood Road at the river end. So I think we can say that we have pinned him down to this location.

AC: I found another clue to Morris’s activities in his 1885 will, which gives his occupation as boat-proprietor. One of the executors of his will was one Sydney Edwards, Boat Builder of Princess Bridge. Sydney Edwards was the eldest son of James Edwards and therefore a member of a very famous rowing family. The Edwards Boatshed was long a feature on the Yarra Bank in Melbourne—you can see it in many old photos of the riverbank.

An article from the Argus in 1928 tells us a little more about the Edwards Brothers and their father James, who learned his trade from a famous boat builder on the Thames in London. A number of the sons were professional sculling champions of Victoria, and Sydney had steered the Scotch College Head of the River crew to victory in 1872 and 1873. My favourite story about Sydney is that he used to give exhibitions on the Yarra River of clever balancing feats like standing on his head in an outrigger.

RK: So there we have it—Christopher Morris was part of a venerable river trade, and connected to some of its leading exponents. The peak of Greek immigration to Melbourne was in the 1950s and 60s—so Christopher Morris—or Christodoulos Moros—was also one of only around 200 Greeks who settled in Victoria before 1900.

_____________________________________________________________________

My Marvellous Melbourne is a production of the Melbourne History Workshop, in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne, Australia. Our thanks to Gavin Nebauer at the Horwood Recording Studio, University of Melbourne, and Andrew Batterham for our theme music. You can find episode notes, further resources, and contact details at our website

mymarvellousmelbourne.net.au.

We’d love to hear from you.

Leave a Reply